At present, the incidence of tuberculosis decreases everywhere, but still remains uneven by countries [10]. Thus, in the US in 2009 the incidence of tuberculosis reached the lowest level in its history – 3.9 cases per 100 000 population, whereas in the Russian Federation according to the data of the Ministry of Health in the same year 2009 it was 82.6 cases per 100 000 [7]. The Kyrgyz Republic is also an endemic area for tuberculosis (95.1-97.4 incident cases per 100 000 population, mortality – 8.6-8.7 deaths per 100 000 population) [5, 6]. The epidemiologic situation causes most concern in such population groups as college students and prisoners, where the prevalence of tuberculosis is much higher than in the country as a whole [2]. Among tuberculosis cases, there is a high proportion of unemployed [7, 9]. However it remains unclear what role in the formation of the tuberculosis infection reservoir is played by the poorest and socially vulnerable population group of homeless persons (persons without fixed abode), which was a reason for undertaking this study [3]. No research on this issue has been done before in the Kyrgyz Republic.

Objectives

The aim of the study was to investigate a medico-social role of homeless persons in the spread of tuberculosis in order to develop new methods of prevention.

Materials and research methods

346 patients with pulmonary tuberculosis were included in the study, who were unemployed and had no fixed dwelling place but received in-patient treatment in the Tuberculosis Hospital and ambulant treatment in the Tuberculosis Dispensary in the city Bishkek for the period 2009-2011. Demographic and clinical data of patients were explored. The data gathered were processed on a computer using the application program package Microsoft Excel, with calculation of Student’s t test.

Research results and discussion

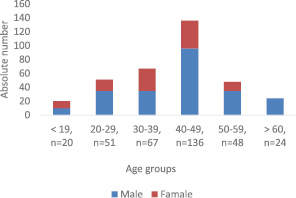

The group consisted of 346 patients with pulmonary tuberculosis who had no fixed abode, males predominated over females, with a significant difference (67.6 % ± 2.5 and 32.4 % ± 2.5, respectively, t -9.9, P < 0.001 ) (figure).

Among age groups, most patients receiving treatment were at ages 30-59 (72.5 % ± 2.5). Patients aged 40-49 years prevailed both over younger patients (30-39 years) (39,3 % ± 2.6 and 19.4 % ± 2.1, respectively, t -5.6, P < 0.01) and over older patients (50-59 years), (39.3 % ± 2.6 and 13.9 % ± 1.9, respectively, t-7.9, P < 0.01), with the difference being significant.

Among study patients, 56.4 % were newly diagnosed cases, 112 cases (32.4 %) were diagnosed previously with treatment already taken. A fact whether medical attention was sought for the first time or repeatedly could not be established for 39 patients (11.3 %) (table 1), who received ambulatory treatment.

Results of sputum test for bacterial excretion were analyzed in newly diagnosed patients and previously treated patients and compared versus tuberculosis patients living in their families serving as a control group (table 2).

Distribution of homeless patients with tuberculosis by sex and age group, n = 346

Table 1

Distribution of homeless patients with tuberculosis as new or past diagnosis, n = 346

|

Tuberculosis patients |

n |

% |

± m |

95 % CI |

P |

|

|

1. |

Newly diagnosed |

195 |

56.4 |

2.7 |

51.2-61.6 |

1-2 < 0.01 |

|

2. |

Diagnosed previously |

112 |

32.4 |

2.5 |

27.5-37.3 |

2-3 < 0.001 |

|

3. |

Unknown |

39 |

11.3 |

1.7 |

8-14.6 |

1-3 < 0.001 |

|

Total |

346 |

100 |

Table 2

Distribution of homeless tuberculosis patients by results of sputum test in relation to new/previous diagnosis in the Kyrgyz Republic, 2009-2011, n = 346

|

Tuberculosis patients |

Total |

Sputum tested |

% |

Sputum positive |

% |

M ± |

95 % CI |

P |

|

|

1. |

Controls |

896 |

609 |

68.0 |

336 |

55.2 |

2.0 |

51.3-59.1 |

1-2 < 0.01 |

|

2. |

Newly diagnosed |

195 |

169 |

86.7 |

136 |

80.5 |

3 |

74.5-86.9 |

2-3 < 0.05 |

|

3. |

Previously diagnosed |

112 |

64 |

57.1 |

51 |

79.7 |

5 |

69.8-89.6 |

1-3 < 0.01 |

|

4. |

Unknown |

39 |

14 |

35.9 |

3 |

21.4 |

11 |

||

|

5. |

All homeless patients |

346 |

247 |

71.4 |

190 |

76.9 |

2.7 |

71.6-82.2 |

1-5 < 0.01 |

Results presented in table 2 show that patients both in the control group and in the homeless group do not always undergo sputum microscopy test (68 % and 71.4 %, respectively, P < 0.01). Every one in 4 patients from the latter group excreted bacillus Kochii with sputum, the frequency being equally frequent both in newly diagnosed and previously treated patients (80.5 % ± 3 and 79.7 % ± 5.0, respectively, P < 0.05). It should be noted that the rates of positive sputum test results for pulmonary tuberculosis bacillus in this group was significantly greater than in patients living in their families (76.9 % ± 2.7 and 55.2 % ± 2.0, respectively, P < 0.01).

Distribution of study patients by clinical forms showed that infiltrative forms of tuberculosis were the most frequent (56.0 ± 3.4 %) including those with destruction of pulmonary tissue (52.4 %), and disseminated tuberculosis constituted 7.9 ± 1.8 % (table 3).

Table 3

Distribution of homeless patients with pulmonary tuberculosis by clinical forms, n = 216

|

Clinical form of tuberculosis |

Absolute number |

Per cent |

|||||||

|

total |

males |

females |

total |

males |

females |

||||

|

% |

m ± |

% |

m ± |

% |

m ± |

||||

|

Infiltrative |

121 |

93 |

28 |

56.0 |

3.4 |

54.1 |

3,8 |

63,6 |

7,3 |

|

Fibrous-cavernous |

78 |

86 |

11 |

36.1 |

3.3 |

50.0 |

3,8 |

25,0 |

6,5 |

|

Disseminated |

17 |

13 |

5 |

7.9 |

1.8 |

7.6 |

2,0 |

11,4 |

4,8 |

|

Total |

216 |

172 (79.7 %) |

44 (20.3 %) |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|||

Table 4

Distribution of homeless patients by results of treatment, n = 216

|

Treatment outcome |

Absolute number |

Per cent |

||||

|

total |

males |

females |

total |

males |

females |

|

|

Absent data |

6 |

5 |

1 |

2.8 |

3.4 |

2.2 |

|

Treatment terminated |

101 |

81 |

20 |

46.8 |

46.9 |

45.4 |

|

Death |

27 |

22 |

5 |

12.5 |

12.5 |

11.9 |

|

Completed treatment |

82 |

64 |

18 |

38.0 |

37.2 |

40.9 |

|

of them: cured |

58 |

44 |

14 |

70.7 |

68.7 |

77.8 |

|

incurable |

24 |

20 |

4 |

29.3 |

31.3 |

22.2 |

|

Total |

216 |

172 |

44 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Table 5

Distribution of homeless patients with pulmonary tuberculosis receiving treatment, by results of sputum microscopy test, n = 392

|

Treatment stages |

Patients subject to the test |

Patients tested |

Smear test results |

||||

|

negative |

positive |

||||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

||

|

Initial stages |

132 |

68 |

51.5 |

43 |

63.2 |

25 |

36.8 |

|

Maintaining stage |

130 |

26 |

20.0 |

18 |

69.2 |

8 |

30.8 |

|

Finalization stage |

130 |

18 |

13.8 |

13 |

72.2 |

5 |

27.8 |

|

Total |

392 |

112 |

28.5 |

||||

The rate of chronic forms of tuberculosis such as a fibrous-cavernous form was 36.1 %. In the female population infiltrative forms were more common but chronic fibrous-cavernous type tuberculosis was less frequent. Such patients present on admission with marked blood spitting turning into pulmonary hemorrhage. 9 patients with infiltrative tuberculosis form had concomitant exudative pleurisy, 7 had pneumonia, one had chronic hepatitis and one had meningitis. In the group of patients with fibrous-cavernous tuberculosis pleurisy was recorded in one and pneumonia in 3 patients.

Among homeless patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, 216 received hospital treatment. Data on results of treatment are shown in table 4.

A high percentage of tuberculosis patients terminating treatment can be noticed – overall 46.8 %, which was slightly higher for males. 27 (12.5 %) patients died during the course of treatment. Treatment was completed in 82 (38.0 %) patients, of whom 58 (70.7 %) had a cure and 24 (29.3 %) were considered incurable.

To test the effectiveness of treatment, the treatment period was divided into stages, because treatment of tuberculosis patients is long-lasting (table 5).

The initial stage is the first 4 months of treatment, the maintaining stage (month 5-6) and the finalizing stage (month 7-8). Sputum microscopy test for carriage of bacilli is obligatory in the course of treatment but often fails to be realized. In the process of treatment, the number of patients receiving this test sharply decreased. At initial stage 51.5 % had sputum microscopy, whereas at the completion stage only 13.8 %. Bacteriosecretion decreased with the progress of treatment, but towards the end of the treatment the rate of bacterioexcreters remained fairly high (27.8 %).

“… It is generally considered that the risk of acquiring tuberculosis is much higher in socially disadapted persons. But in available literature in phthisiatric areas no definition of socially disadapted groups is given and no substantial evidence is presented for the prevalence of tuberculosis in these groups being higher than in the larger populations.

Regarding individual behavior “social diasadaptation” can be seen as acts of individuals that are forbidden by legal and moral norms, laws of communal life. These include various deviant behaviors: alcoholism, drug abuse, suicide, amoral behavior, child homelessness and neglect, difficult children and adolescents, any violation of social norms” (Doktorova N.P., 2007).

Our study showed that pulmonary tuberculosis occurs at all ages of the adult population group of homeless persons in the Kyrgyz Republic, and the highest tuberculosis detection rate is found for patients aged 40-49 years. Studies on the similar topic report the younger age range of 35-44 years and that without great gender difference (K.A. Smetanina, 2013). Naturally, tuberculosis patients of this age endure the lack of normal social conditions harder and their disease has a more severe course, manifesting itself in the ineffectiveness of treatment – Koch’s bacillus is excreted both by newly diagnosed and previously treated patients due to chronic forms of tuberculosis common in them and the predominance of destructive forms. Considering that pleurisy and meningitis are extrapulmonary forms of tuberculosis it means that the combined pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis form is rather frequent in homeless persons. The main reason for low cure rate is treatment abandoning (for various reasons such as inclination to vagrancy and falling back into alcoholism and drug addiction, underestimation of one’s own condition patients leave hospital without permission), a high level of advanced forms of pulmonary tuberculosis refractory to modern methods of therapy (V.A. Nikolaev, 2011).

Thus, socially insecure persons (homeless persons without fixed abode) have a high level of pulmonary tuberculosis morbidity. They lead in such conditions as chronic tuberculosis morbidity with pulmonary tissue destruction and a high rate of bacterioexcretion. Compared to normal patients, they have the lowest rates of clinical cure, closure of destructive cavities, release from clinical observation because their bacterioexcretion practically never stops [4]. Besides, in the homeless cohort a high level of patients with early and late relapses is observed. The severity and clinical features of tuberculosis in homeless persons are mainly explained by their lack of organization and inclination to the vagrant style of life. In conclusion, we will note that the homeless cohort is an infection reservoir of sorts contributing to the growth of the incidence, prevalence and mortality from tuberculosis.

Recommendations

Not to investigate but to improve social and living conditions – special houses, warm doss-houses, better nutrition, vitaminization, continuous monitoring of patient’s behavior at different stages of treatment, airing and disinfection of rooms. To conduct a range of anti-tuberculosis measures (social support of the tuberculosis control program, creation of rehabilitation centers, educational activities and awareness raising). Continuous monitoring should be maintained during treatment of refugees and homeless persons. To use teamwork method and mobile fluorography. To establish specialized hospitals (units), rehabilitation centers and care homes for those who have suffered tuberculosis and those with chronic forms of tuberculosis.