This scientific problem was considered from the perspective of art criticism [1, 3, 8, 9 et al], but the legal aspects of the reform have not yet become the subject of scientific research. The purpose of the article: to analyze the conditions of the reform in the Siberian North.

Tobolsk’s ecclesiastical seminary was founded in 1743 on the basis of pontifical class, which had existed since 1703. An icon-painting class was officially opened at the seminary in 1800, but in fact the workshops, where masters shared their experience and skills with their disciples, had existed much earlier, since XVII century: huge Siberian region, captured with orthodox missionary, needed a large number of icons. However, whilst being an instrument of the spiritual impact on society, ecclesiastical orthodox art was under the control of the church and the government, this is why the formation of icon-painting tradition in Siberia became a complicated process.

On a national scale, in the beginning of XVII century the church paintings (frescos, iconography, mural painting) became the most developed kind of religious fine art in Russia; its canons and standards had already been worked out. An accurate system of religious art governance was also developed; on a national scale “Ikonny Prikaz” (1620 – 1640) gave birth to “Icon Chambers” at the Kremlin Armory, where the lessons were given. It is a common fact that tzar Aleksey Mikhailovich showed a great interest in the learning process of this school [3: 382]. Prokopiy Cherin, Fyodor and Istoma Saviny and others graduated from this school and through the Stroganov’s “Icon Chambers” shared their knowledge with Siberian icon painters. There was a professional hierarchy of the icon painters in such schools: “appointee”, “apprentice”, “iconpainter”, “master” etc., which corresponded to the established traditions and the spiritual idea of icon painting.

By the beginning of Peter the Great’s reforms there were also the manuals on icon painting – “The Icon-Painter’s Guides”, which represented the collection of samples, which specified all the details of the canonical images of various individuals and events (up to the letter techniques), and were developed by the beginning of the government reforms of Peter I. There were two types of the Icon-Painter’s Guides: explanatory and illuminated. An illuminated guide was a kind of an album depicting the saints, where all the images were placed in a chronological or thematic order. An Icon-Painter’s Guide contained not only the instructions on the techniques of the icon painting, but it also comprised the masters’ behavior, regulating strictly their whole life. It was stated that every “kind icon painter” should have his spiritual father and communicate with him as often as possible. Icon painter was recommended to be married “in order to avoid lust”. In this respect, and also in some others, an icon painter became equal to a priest. His model of behavior was thoroughly prescribed: an icon painter should be sober, conscientious, selfless, God-fearing and lead an exemplary way of life.

Considering the role of the Stroganovs in the history of Siberia, the Stroganovs’ icon-painting tradition was specifically widespread in the region. Stroganov’s original didn’t yield to the famous Siyskiy’s original in its’ significance – they were both considered to be “the best” in the clergy community, but the Stroganovs’ was on the second place [3: 381]; apart from it, Novgorodian icon-painting school became traditional. Within these merchant traditions a very rich decoration of riza was introduced. For example, one of the icons of the first Siberian governor M.P. Gagarin cost 130 thousands gold roubles [7: 41].

The beginning of the new stage in the development of the religious art is connected with the reforms of Peter I. One of the reasons for the reform was the appearance of a great number of non-professionally painted icons and also the ignorance of Icon-Painter’s Guides by the painters themselves, which struck the prestige of the church badly. Moreover, the reform could have contributed to the replenishment of the state treasury, therefore there was an attempt to spread it on heterodox religious art: Muslim, Buddhism, Judaism and Shamanism, but this was done in vain. Consequently, in 1707 (13th February and 26th April) Peter I issued two decrees which regulated only icon painting [3: 319, 320]. The new management body was established by the decree made on 26th April, 1707; it was called “The House of icon-painting fixing”. There was also a new post of the principal introduced, who got the right “to send the decrees to every town on his behalf” and to control the artistic quality of icons. The principal was inferior to the spiritual authority and was given clerks, both young and old, watchmen and soldiers of the Moscow garrison to be his assistants. Obviously, thispersonnel didn’t correspond with the mission of the new managing body. Ivan Zarudny, which headed the House of icon-painting fixing, got an instruction form the Tzar. The essence of it was in twenty paragraphs, which were partly spread on the Western Siberia, while the second part turned out to be absolutely inapplicable due to the local peculiarities.

Paragraph 1 required to create lists of icon painters of the Russian government [3: 319]. Since the introduction of this order the number of icon painters in Siberia began to be recorded. Thus, according to the population census, conducted in 1788, there were 4 painters among tradesmen and 5 painters among craftsmen; in Tyumen – 3 icon painters, 2 apprentices and 1 disciple; by 1711 there were two more painters which appeared in Tyumen’s census books [9].

Paragraphs 2–7 established a personal responsibility of icon painters for their work and distributed them into three categories. They also introduced a certification of the masters together with the delivery of the relevant documents (“lists”) and other requirements, necessary for icon painters’ organization: “Send the orders with the “marks”, or in other words, with stamps made for the three categories, and with the names of iconographers, to bishops and to monasteries, to the priestsof the collegiate parish churches; without these “marks” the admission of icons is prohibited”[3: 319]. It was supposed that there should be a stamp of icon painters on each icon, which would confirm his qualification – a specific quality mark.

This condition, however, was contrary to the rules of icon painting: according to the tradition, there should be no painter’s signature on the icon. At the best, a painter made a remark like this: “Painted by…” (it was supposed that the icon itself proceeded from God, who controlled the hand of icon painter), or there was a name of saint, whom the painter “wanted to reveal to the whole world through the icon” [8: 243]. In conditions of Tobolsk’s icon-painting workshops these terms were difficult to accomplish because there were just a few masters, and for some of them icon painting wasn’t even the core business. For example, by the end of XVII century – beginning of XVIII century a horse kazak N. Murzin and a bachelor V.N. Bogdanovych [9] were doing icon painting, and this was accepted by the local spiritual authority.

The only statement of this instruction which could be partially accomplished, but only after the death of Peter I, was the certification of the masters: everyone who finished the icon-painting class of the Tobolsk’s ecclesiastical seminary, established in 1800, got a certificate. But even in the period of Peter’s reign this was not enough for being included onto the emerging iconographer’s workshop, because all certificates were not considered to be the lists of certification. Moreover, Peter I introduced a fee for getting “the lists with printed stamps”: “1st degree – 1 rouble, 2nd degree – 75 copecks, 3rd degree – fifty copecks per man” [3: 320].

The rule, according to which “the lists” were given in the House of icon- painting fixing, made the situation even more complicated. Considering the fact that going there on foot would take 1,5–2 years and on a dray-cart – a few months (for example, it took the priest Avvakum 13 weeks to get to Tobolsk) [4: 16], including also significant material costs; for local icon painters this condition was practically impossible to execute. In fact,

the certificated masters were given a special salary as a reward, independently from the region where they lived. This is why after getting a cherished “list” it was better for the master not to return to Siberia. All this impeded the execution of the instructuion’s statements.

Paragraphs 8–10 revealed prohibitions for the masters who didn’t get certificates to paint icons secretly at home[3: 320]. They were allowed to work in the official icon-painting workshops, but there were some restrictions introduced: only those icon painters, who had 1st degree, had the right to take responsibility over the whole church’s decoration (frescos, mural painting, icons and also carpentry work, carving and gilding of the iconostasis). However, due to the shortage of icon painters with the 1st degree in Western Siberia, this job was obtained by the mostworthy masters, but provided that Tobolsk’s metropolitan gave his blessing. Paragraphs 11–15 regulated the process of passing on the masters’ experience to their disciples; it was prohibited to stop improving one’s skills of icon painting. Paragraphs 16–20 prohibited selling icons without special “marks” – certified stamps [3: 320].

The positions fixed in paragraphs 11–15 and 16–20, which were more focused on the replenishment of the state treasury than on fighting the wrong way of icon painting, were absolutely inapplicable to the painters in Western Siberia. Their realization threatened the destruction of the region’s existing traditions of icon painting. It would have also brought church painting back to its original state, when icons were imported to Siberia. Meanwhile, in the first quarter of the XVII century the massive import of icons to Siberia had stopped, because this necessity provided by Stroganovs’ “Icon Chambers” which were situated in the Urals. For example, according to the posthumous inventory of the property which belonged to Maxim YakovlevichSavin, made on 16th July, 1627, there were about 500 of both finished and uncompleted icons in one of the workshops [9].

As a result, the nonfulfillment of the Tzar’s instruction gave an ambiguous result. On the one hand, the region’s distant location, autonomy of the local authority and its lack of control – all that by XVII century had already created an opportunity for avoiding the execution of the order. On the other hand, the authoritarian rule of Peter I had already been felt: the tragic fate of he first Siberian governor M.P. Gagarinin, who was executed for his arbitrariness, indicated that there was a real threat for Tobolsk’s clergy to fall out of favor too, especially when it came to the government finance [7: 121]. The situation became more complicated because of the Tzar Peter’s notorious attitude towards the orthodox church: Peter allowed to remelt the church bells into cannons. In this respect Tobolsk’s clergy showed a great courage – they acted in a way, which seemed to be the most rational and justified under these circumstances in order to save the icon painting class and to continue creating icons. Therefore there still were no stamps on the Western Siberia’s icons. For instance, both Tobolsk and Tyumen’s museums don’t have such icons. Moreover, Tyumen’s orthodox priests also deny having stamps on the icons in the functioning churches.

The bureaucratic principle of the fine art’s regulation didn’t bear any fruits: the Icon Painter’s Guides were still being violated, the taxes were not paid. In 1722 Peter I had to make an announcement about the new stage of “icon-painting reform” in the presence of the Senate and the Synod. In fact, in many respects it was quite similar to the previous one. The researchers named the sanctions, which were presented within the reform, as “the censorship of icon painting” [5]. By the Holy Synod’s order a special extract about saints’ depiction was taken out of the existing instructions, written in 1667. Synod, for its part, complemented the extract with the list of prohibited icons, which were painted clumsily and ineptly [3: 319].

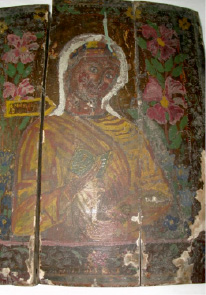

By the resolution of Synod, made on 21st May 1722, it was prohibited to have carved, trimmed, hewn and sculptured icons at home, made by un skilful or insidious iconographers, “because there are no painters chosen by God, and rude ignorants are willing to take their place” [8: 60]. However, Siberian spiritual authority couldn’t completely execute this resolution because of its actual impracticability: “folk” icons (painted by common people) were a mass phenomenon. For example, there is an icon called “Chernushka” (an image of Mother of God, which was painted in Smolensk), which is kept in the collection of the museum of archeology and ethnography, which belongs to the Tyumen State University [2, Inv. № КП-327]. It is dated not just by the post-Petrine time, but by the end of XIX – beginning of XX century. The second example is the icon called “Krasnushka” (Christ Pantocrator) [2, Inv. №КП-314]. The presence of wooden sculpture (“carved icons”) in the collections belonging to Western Siberia’s museums also confirms this tendency and characterizes the peculiarities of Western Siberia’s icon-painting traditions [6].

The icon called “Krasnushka” (Christ Pantocrator)

The existence of icon-painting class in Tobolsk’s penitentiary was another bright feature: it was called “a small icon-painting atelier” [4: 75]. It was created to educate the convicts both spiritually and morally, and also to attach them to Orthodoxy. The process was supervised by the Tobolsk’s spiritual seminary. The status of the prison icon painter needed to be deserved through repentance, confession, spiritual and physical purification, which were conducted through long fasting: according to the orthodox rules, the fasting before painting an icon could last for 40 days. Moreover, a man willing to become an icon painter ought to refrain from violating prison rules and law. Among the favorite icons, which were painted in prison, was the image of saint Anastasia. In ancient Rome she secretly came to prisoners and looked after them: fed them, cured and washed. She was depicted with a cross in the right hand and with a holy oil in the left. With this oil she cured wounds [1: 21].

Thus, despite all the government’s endeavors, the iconpainting on the territory of Tobolsk and Tyumen’s eparchy had been saving its originality for centuries, whilst developing in its own way. Icon-painting class was the central link, where the working process was conducted according to the rules of Stroganov and Novgorod’s schools. However, the regional peculiarities of icon painting had a large influence on the creative process and the meaning of the icon created.

Implemented with the support of the Grant of the President of the Russian Federation MK-3655.2019.6.